اولین انتشار: 01 ژوئیه 2022

جهت گیری خلاق میزانی است که افراد مختلف به سمت فعالیت های خلاقانه (مانند هنر، موسیقی) کشیده می شوند. با توجه به محدودیتهای آزمایشی، ما اطلاعات نسبتا کمی در مورد جهتگیری خلاقانه در سطح کودک داریم. ابزار بزرگسالان اغلب زمان صرف شده در فعالیت های خلاقانه را اندازه گیری می کنند، اما این روش برای کودکان نامناسب است زیرا اوقات فراغت آنها اغلب توسط والدین دیکته می شود. برای غلبه بر این مسئله، ما یک معیار کاملاً جدید از جهت گیری خلاق ابداع کردیم، آزمون جهت گیری خلاق کودکان: هنری (C-COT: Artistic). این کار کوتاه که برای کودکان 6 ساله مناسب است، انگیزه های خلاقانه کودکان را به سمت فعالیت های هنری مستقل از تأثیر والدین برمی انگیزد و امتیاز کمی را ارائه می دهد. ما اندازه گیری خود را برای بیش از 3000 کودک 6 تا 10 ساله به کار بردیم، جایی که قابلیت اطمینان قوی را نشان داد، که نشان می دهد جهت گیری خلاق یک ویژگی پایدار در طول زمان است. ما نشان میدهیم که جهتگیری خلاق نیز تحتتاثیر گروه کلاس، سن، و جنسیت قرار میگیرد، اما تحت تأثیر وضعیت اجتماعی-اقتصادی یا تغییرات فصلی قرار نمیگیرد (تست پاییز در مقابل بهار). ما همچنین نشان دادیم که جهتگیری خلاق با تفکر خلاق (تفکر واگرا)، شخصیت خلاق (باز بودن به تجربیات، بهویژه ویژگی فرعی زیباییشناسی)، و درگیریهای خلاقانه در خانه همگرا میشود. ما تست خود را در اینجا به طور کامل به عنوان معیاری ساده، سریع و قوی برای جهت گیری هنری خلاقانه در کودکان ارائه می کنیم.

برای حداقل 100 سال، روانشناسان به دنبال کشف جوهره خلاقیت بوده اند، با پایه های این علم به سنت های یونانی و رومی اولیه (فینکه، وارد، و اسمیت، 1992؛ Kneller، 1965؛ مک کارتی و پیتاوی، 2014). و مطالعات خلاقیت را از منظرهای متعدد توصیف کرده اند و تصویری جامع از زوایای مختلف ایجاد می کنند. یک تعریف پذیرفته شده این بوده است که خلاقیت ایده یا محصولی بدیع و مناسب/مفید/ارزشمند ایجاد می کند (یونگ، مید، کاراسکو، و فلورس، 2013؛ رانکو و یاگر، 2012؛ استین، 1953؛ استرنبرگ و لوبارت، ویگوتسکی، 1999; ، 2004) و شامل ایدهها یا محصولاتی از طیف گستردهای از حوزهها، از جمله هنرهای خلاقانه، علوم، ریاضیات یا حل مسائل روزمره است. از دیدگاهی کاملاً متفاوت، کافمن و بگتو (2009) و استاین (1953) خلاقیت را به یک سلسله مراتب کیفی، با نوابغ خلاق در راس (مانند داوینچی) تا متخصصان خلاق (مثلاً صنعتگران)، تا خلاقیت روزمره تعریف کردند. به عنوان مثال، حل مسئله)، و در نهایت به رشد خلاقیت در دوران کودکی (اغلب به عنوان پتانسیل خلاق شناخته می شود). با این حال، شاخه دیگری از تحقیقات مربوط به جنبه های انگیزشی خلاقیت است (آمابیل، 1983)، که نشان دهنده انگیزه های روانی است که خلاقیت را تحریک می کند. در نهایت، یکی از رویکردهای مفید معاصر این بوده است که خلاقیت را به سه حوزه اصلی تقسیم کنیم (کروپلی، 2000): تفکر خلاق (یعنی توانایی تولید ایده های خلاق)، محصولات خلاق (یعنی توانایی تولید خروجی خلاق)، و فرد / جهت گیری خلاق (یعنی انگیزه ای که افراد خاصی را به سمت فعالیت های خلاقانه از جمله ویژگی های شخصیتی مرتبط با خلاقیت سوق می دهد). مطالعه فعلی ما جنبه ای از این مؤلفه سوم را بررسی می کند – جهت گیری های فردی کودکان به سمت فعالیت های هنری خلاق.

خلاقیت به وضوح از فردی به فرد دیگر متفاوت است و تفاوت های فردی می تواند در اوایل کودکی ظاهر شود. با این حال، درک این تفاوت ها در کودکان چالش هایی را به همراه دارد. تعدادی آزمون و پرسشنامه خلاقیت برای کودکان وجود دارد، اما اکثریت انواع تفکر خلاق (مانند آزمون تورنس تفکر خلاق، TTCT؛ تورنس، 2008) یا تفکر/محصولات خلاق (تورنس، 2008؛ شهری و جلن، 1996) را اندازه گیری می کنند. ). تعداد بسیار کمی از آزمونهای دوران کودکی بر جهتگیری خلاق تمرکز میکنند – که ویگوتسکی برای اولین بار در سال 1930 به عنوان “میل کودکان به ترسیم و ساختن داستان” (ویگوتسکی، 2004) و آمابیل (Amabile، 1983؛ Amabile و همکارانش) توصیف کرد. ., 2018) از آن زمان به عنوان “انگیزه وظیفه” نامیده می شود. در نتیجه، ما در مورد اینکه چگونه کودکان در تمایلات فردی آنها برای درگیر شدن در مشاغل خلاقانه تفاوت دارند، اطلاعات کمی داریم. با این حال، درک این ویژگی می تواند بینش ارزشمندی در مورد تمایلات کودکان به دست دهد. و به سادگی درک این موضوع که کودکان مختلف ارزشهای متفاوتی را برای فعالیتهای خلاقانه قائل میشوند، میتواند ما را به درک بهتر لذتهای فردی و مجاری فردی آنها به سوی شادی سوق دهد.

یک چالش خاص در اندازه گیری جهت گیری خلاقانه کودکان به سردرگمی برمی گردد که هنگام اندازه گیری کودکان به وجود می آید، که در اندازه گیری بزرگسالان ایجاد نمی شود. در ابزار بزرگسالان، جهت گیری خلاق را می توان با درگیری اندازه گیری کرد، یعنی با کمی کردن زمانی که فرد صرف فعالیت های خلاقانه می کند – چه برای اوقات فراغت یا برای اشتغال (بیتی، 2007؛ دالینگر، 2003؛ هوسوار، 1979؛ لونک و مایر، رانکو و آلبرت، 1985، تیلور و الیسون، 1983). منطق در اینجا این است که تعامل یک نشانه بیرونی مفید جهت گیری خلاق است (یعنی افرادی که خلاقیت بیشتری دارند بیشتر درگیر می شوند). در واقع، ما میتوانیم جهتگیری خلاقانه را با نگاه کردن به مشارکت در طیف وسیعی از فعالیتهای خلاقانه درک کنیم. برای مثال، فهرست بررسی فعالیتهای خلاق، مشارکت در شش حوزه خلاق را در بزرگسالان جوان و کودکان بزرگتر (ادبیات، موسیقی، نمایش، هنر، صنایع دستی و علم؛ رانکو و آلبرت، 1985) اندازهگیری میکند. با این حال، ارزیابی جهت گیری خلاقانه در کودکان کوچکتر به ویژه چالش برانگیز بوده است، زیرا مشارکت آنها در فعالیت ها عمدتاً توسط والدین آنها (و در واقع وضعیت مالی والدین آنها) دیکته می شود. از این رو، کودکی که هر آخر هفته را در کلاس هنر یا گروه نمایش می گذراند، ممکن است در واقع نسبت به کودکی که اصلاً در چنین کلاس هایی شرکت نمی کند، خلاقیت کمتری داشته باشد. این باعث میشود معیار «زمان صرف شده» در شرکتکنندگان جوان بیارزش باشد، زیرا در عوض نشاندهنده تلاشها و توانایی والدین آنها برای ایجاد مشارکت است.

اگر تلاش برای استنباط جهت گیری خلاقانه نه از تعامل، بلکه از دستاوردهای خلاقانه (یعنی با این فرض که افراد خلاق تر به دستاوردهای بیشتری دست پیدا می کنند) مشکل مشابهی پیش خواهد آمد. علیرغم معیارهای فراوانی از دستاوردهای خلاق (هوسوار، 1979؛ مایکل و کولسون، 1979؛ تیلور و الیسون، 1968)، این موارد نیز اگر برای سنجش جهت گیری در کودکان مورد استفاده قرار گیرند، باز هم با توجه به شرایط خانوادگی (یعنی امکانات مالی) و در واقع همچنین، گیج خواهند شد. سن کودک (کودکان بزرگتر زمان بیشتری برای درگیر شدن/دستیابی به آنها داشته اند؛ سیکسزنت میهالی، 1988؛ لارو، 2002؛ ریچاردز، گارات، هیث، اندرسون، و آلتینتاش، 2016). در نتیجه ، اگرچه ما می توانیم جهت گیری خلاقانه را در بزرگسالان برآورد کنیم (Dollinger ، 2003 ؛ Hocevar ، 1979 ؛ Hocevar & Michael ، 1979 ؛ Lunke & Meier ، 2016) ما به هیچ وجه برای اندازه گیری جهت گیری خلاقانه در کودکان تلاش می کنیم.

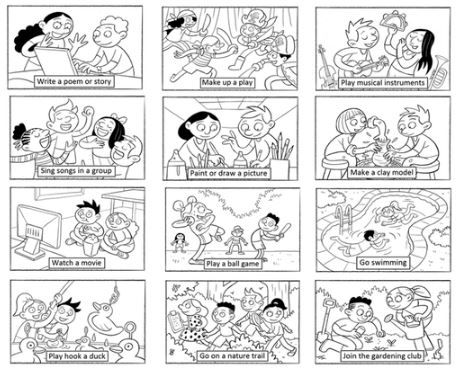

از آنجایی که ثابت شده است اندازه گیری جهت گیری خلاق از طریق معیارهای معمول بزرگسالان (“زمان صرف” یا “دستاوردهای به دست آمده”) دشوار است، ما این چالش را برای ابداع یک ارزیابی کاملاً جدید از دوران کودکی برای غلبه بر این دشواری انجام دادیم. آزمون جدید ما جهت گیری کودکان را به سمت فعالیت های خلاقانه مستقل از جدول زمانی والدین اندازه گیری می کند و ما از آزمون خود برای درک تمایلات خلاقانه بیش از 3000 کودک 6 تا 10 ساله استفاده کردیم. برای پیشبینی نتایج، نشان خواهیم داد که آزمون ما واقعاً میتواند تفاوتهای فردی در جهتگیری خلاق/هنری را مشخص کند، و این موارد در مقابل سایر معیارها و همچنین نشان دادن تفاوتهای جمعیت شناختی در بین جنسیت و سن تأیید میشوند. در وظیفه ما، به کودکان تصاویری از 12 فعالیت مختلف، نیمی از فعالیت های خلاقانه/هنری و نیمی فعالیت های غیر خلاق ارائه شد. از بچه ها خواسته شد تصمیم بگیرند که کدام فعالیت ها را برای انجام یک روز سرگرم کننده تخیلی انتخاب کنند (“تصور کنید که در یک روز سرگرم کننده بیرون می روید، و اینها فعالیت هایی هستند که می توانید انتخاب کنید”). به کودکان دستوراتی داده شد تا به آنها اجازه دهد به طور معناداری به همه 12 فعالیت در یک لیست مرتب شده از بیشترین تا کمتر ترجیح داده شده رتبه بندی کنند. سپس آزمون خود را نمره دادیم تا میزان گرایش هر کودک به فعالیت های خلاقانه را کمی کنیم.

در مطالعه خود، ما بر فعالیت های خلاقانه در هنر (به جای ریاضیات، علوم یا سایر رشته ها) تمرکز کردیم و این به دلایل مختلف بود. اولاً، محققان خلاقیت از Hocevar (1979) نشان دادهاند که فعالیتهای هنری ممکن است به عنوان فعالیتهای خلاق کهن الگو در نظر گرفته شوند، زیرا آنها بزرگترین گروه از آیتمها را در هر معیاری از فعالیتهای خلاق، برای بزرگسالان یا کودکان و به ویژه برای کودکان نشان میدهند. که در آن اکثریت قاطع هستند، به عنوان مثال، Dollinger، 2003، Dollinger، Palaskonis، و Pearson، 2004a، Runco، 1987؛ Dollinger، Urban، و James، 2004b). دوم و مرتبط، در حالی که یک کودک معمولی اغلب خلاقیت مبتنی بر هنر را تجربه می کند، آنها تجربه نسبتا کمی از خلاقیت غیر هنری که معمولاً توصیف می شود، خواهند داشت. ما می توانیم این را با نگاه کردن به موارد علمی خلاقانه، به عنوان مثال، از فهرست بیوگرافی رفتارهای خلاقانه Batey (مانند “تولید یک نظریه”، “انتشار یک مقاله علمی”؛ Batey، 2007) یا اقدامات رانکو برای کودکان بزرگتر (مانند، “آزمایش اصلی را انجام داد”؛ رانکو، 1987). اگرچه میتوان نسخههای کودکمحور از این فعالیتها را ایجاد کرد (مثلاً سنتز ساختارهای شیمیایی از بلوکهای ساختمانی)، اینها احتمالاً برای یک کودک خردسال نسبتاً کمتر از مثلاً نقاشی یا طراحی آشنا هستند. ثالثاً، اگر بخواهیم چنین فعالیتهایی (مانند فعالیتهای علمی با محوریت کودک) را در نظر بگیریم، تشخیص اینکه فعالیت مورد نظر به خودی خود خلاقانه بوده است، دشوار خواهد بود، زیرا آزمون ما برای کودکان خردسال از تصاویری استفاده میکند که عملاً بدون آنها وجود ندارد. متن از این رو، تصویری از کودک که با استفاده از بلوکهای ساختمانی ساختارهای شیمیایی میسازد (یا افزودن دو ماده شیمیایی در آزمایشگاه، یا انجام آزمایشهایی در طبیعت و غیره) در مؤلفه خلاقانهاش نامشخص است. در مقابل، آیتمهای (هنری) خودمان نشاندهنده فعالیتهای خلاقانهای هستند که برای هر کودکی به راحتی و بدون توضیح، درک میشود. در نهایت، چارچوب آزمایش ما به طور اساسی به ما امکان میدهد تا کودکان را به دور از تأثیرات والدین/اجتماعی-اقتصادی ارزیابی کنیم، اما لزوماً شامل قرار دادن فعالیتهایمان در یک روز سرگرمی خیالی است. بنابراین، ما طبیعتاً محدود به انتخاب فعالیتهایی هستیم که معمولاً با این چارچوب مطابقت دارند، و فعالیتهایی مانند نقاشی نمونههای رایجتر از علم هستند (اگرچه هر دو از نظر نظری امکانپذیر هستند). به طور خلاصه، به همه این دلایل، فعالیتهای خلاقانه ما، فعالیتهای خلاقانه هنری هستند، زیرا این فعالیتها برای سن مناسب هستند، با زمینه مشترک هستند و به راحتی به عنوان خلاق برای کودکان به تصویر کشیده میشوند.

همه کودکان همگروه ما آزمون ما را در یک جلسه اولیه تکمیل کردند و حدود 1000 نفر از آنها نیز تقریباً 9 ماه بعد (برای اندازه گیری پایایی آزمون-بازآزمایی در طول زمان) برای بار دوم آزمایش مشابهی دادند. در مطالعه دوم، به همان کودکان آزمون دیگری از نوع تفکر خلاق نیز داده شد (یعنی تفکر واگرا، با استفاده از وظیفه استفاده های جایگزین از TTCT؛ تورنس، 2008). این نه تنها به ما امکان می دهد ارزیابی کنیم که آیا جهت گیری خلاق با تفکر واگرا مطابقت دارد یا خیر، بلکه این فرصت را نیز به ما می دهد تا آزمایش کنیم که آیا معیار جدید ما اعتبار همگرا با سایر ابزارهای خلاقیت دارد یا خیر. علاوه بر این، به کل گروه ما نیز یک تست شخصیت داده شد تا همگرایی بین معیار جهت گیری خلاقانه خودمان و ویژگی های شخصیتی که معمولاً با خلاقیت مرتبط است (به عنوان مثال، گشودگی به تجربیات؛ زیر را ببینید). ما همچنین بیش از 700 نفر از والدین یا مراقبان آنها (از این پس “والدین”) را آزمایش کردیم تا رتبهبندی والدین از شخصیت کودکان و همچنین اندازهگیری میزان مشارکت کودکان در فعالیتهای خلاقانه در خانه را بدست آوریم (به زیر مراجعه کنید).

برای اندازه گیری شخصیت خود، ما انتخاب کردیم که 44 مورد فهرست پنج بزرگ تعریفی را برای کودکان اجرا کنیم (Def BFI-44-C؛ رینالدی، اسمیز، کارمایکل، و سیمنر، 2020؛ جان، داناهو، و کنتل، 1991؛ جان، نائومان، و سوتو، 2008؛ سوتو، جان، گاسلینگ، و پاتر، 2008). این ابزار خودگزارشدهی شخصیت کودکان را با پنج عامل اندازهگیری میکند و یکی از این عوامل – گشودگی به تجربه – به ویژه با خلاقیت و هوش مرتبط است (کاسپی، رابرتز و شاینر، 2005؛ مککری و کاستا، 1987). یک پرسشنامه معادل برای والدین کودکان (BFI-44-Parent؛ موجود در https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~johnlab/measures.htm؛ نگاه کنید به جان و همکاران، 1991، 2008؛ جان و سریواستاوا، 1999) زیرا رتبهبندیهای والدین گاهی اطلاعات بیشتری را فراتر از کودک دارد (مارکی، مارکی، تینزلی و اریکسن، 2002). ما این ابزارهای شخصیتی را بهویژه انتخاب کردیم زیرا ساختار پنج عاملی بزرگ شخصیت هم در بزرگسالان و هم در کودکان تأیید شده است (ابه، 2005؛ آبه و ایزارد، 1999؛ دیگمن و تاکموتو-چاک، 1981؛ هالورسون و همکاران، 2003؛ جان. و همکاران، 2008؛ جان، کاسپی، رابینز، موفیت، و استوتامر-لوبر، 1994؛ مارکی و همکاران، 2002؛ شولت، ون آکن، و ون لیشوت، 1997) و این اقدامات خاص (دف BFI-44-C) و BFI-44-Parent) بهعلاوه بر روی همان گروه از کودکانی که در اینجا آزمایش شدهاند تأیید شدهاند (رینالدی و همکاران، 2020). در نهایت، با ویژگی مورد علاقه خود (باز بودن به تجربه)، ما همچنین زیرشاخه های باز بودن به زیبایی شناسی و گشودگی به ایده ها را بررسی خواهیم کرد (سوتو و جان، 2009). ما پیشبینی میکنیم که رابطه نزدیکتری بین جهتگیری خلاق و زیرشاخه قبلی پیدا کنیم، زیرا گشودگی به زیباییشناسی به ویژه با تمایل هنری مرتبط است (کافمن و همکاران، 2016).

ما همچنین بررسی کردیم که آیا تفاوتهای فردی در جهتگیری خلاقانه از کودکی به کودک دیگر را میتوان بر اساس سن، جنسیت و محیط تشخیص داد. تفاوتهای جنسیتی اغلب در جنبههای تفکر خلاق، تعامل و فعالیتها دیده میشود (بائر و کافمن، 2008؛ چان، 2005؛ رانکو، کراموند، پاگنانی، 2010، رانکو، 1986)، و با این واقعیت که علایق با افزایش سن تغییر میکنند، در تعامل هستند. هیلتون و برگلند، 1974؛ تریسی، 2002؛ تریسی و وارد، 1998؛ واینبرگ، 1995). ما همچنین سه اثر محیطی را بررسی کردیم: اثرات کلاس درس، اثرات اجتماعی-اقتصادی و اثرات فصلی. اولی مورد توجه بود زیرا به عنوان مثال، سبک های تدریس بر خلاقیت کودکان تأثیر می گذارد (ریو، 2009)، و تأثیرات قابل توجهی در مدرسه یا کلاس در تعدادی از اقدامات خلاقیت از جمله تولید نقاشی (Gralewski & Karwowski، 2012) و تفکر واگرا (کوهن و هولینگ، 2009). نمونه ما همچنین در زمینه اجتماعی-اقتصادی متفاوت بود، و ما فرض کردیم که این می تواند بر جهت گیری خلاق با توجه به سطوح مختلف منابع والدین تأثیر بگذارد. اگر جهتگیری با تجربه قبلی مرتبط باشد، ممکن است متوجه شویم که خانوادههایی که منابع مالی بیشتری برای هدایت شغلهای خلاقانه دارند (مثلاً کلاسهای نمایش) ممکن است آنهایی باشند که فرزندانشان بیشتر به این سمت گرایش دارند. از طرف دیگر، ممکن است برعکس این موضوع را بیابیم: اینکه کودکانی که از امکانات مالی مشابهی برای شرکت در این فعالیتها برخوردار نیستند، تمایل بیشتری به آنها دارند. در نهایت، ما این فرصت را داشتیم تا اثرات فصلی را بررسی کنیم زیرا گروه ما در ترم پاییز (اکتبر-دسامبر) یا ترم بهار (ژانویه-آوریل) آزمایش شد. بنابراین ما آزمایش کردیم که آیا فصل (با تفاوت آن در میانگین نور روزانه خورشید) بر جهت گیری خلاق تأثیر می گذارد یا خیر (برای تأثیر نور بر خلاقیت به Kombeiz & Steidle، 2018 مراجعه کنید).

به طور خلاصه، ما جهت گیری کودکان به فعالیت های خلاقانه را بررسی کردیم و معیار جدیدی را ابداع و تأیید کردیم که آن را آزمون جهت گیری خلاق کودکان: هنری (C-COT: Artistic) نام گذاری کرده ایم. ما با آزمایش گروه زیادی از کودکان (6 تا 10 ساله) در طول تقریباً 9 ماه، پرسیدیم که آیا جهت گیری خلاق یک ویژگی پایدار است یا خیر. با انجام این کار، هدف ما نشان دادن قابلیت اطمینان تست-آزمون مجدد ابزارمان، و همچنین تأثیرات جمعیت شناختی و دیگر موارد است. در مطالعه دوم، ما رابطه بین جهت گیری خلاق و تفکر واگرا خلاق (به عنوان مثال، کار استفاده های جایگزین از TTCT)، شخصیت خلاق (ویژگی گشودگی به تجربیات، در Def BFI-44-C و BFI-44-) را اندازه گیری خواهیم کرد. والدین)، و مشارکت خلاقانه در خانه (با استفاده از پرسشنامه مشارکت خلاق در خانه؛ به روش ها مراجعه کنید). این یافتههای همگرا، اندازهگیری ما را نیز تأیید میکند. روش ها و نتایج ما در زیر توضیح داده شده است.

مطالعه 1: آیا جهت گیری خلاق یک ویژگی پایدار است و آیا اثرات جمعیتی، زیست محیطی و اجتماعی-اقتصادی را نشان می دهد؟

مواد و روش ها

شرکت کنندگان

تست در دو جلسه انجام شد. در جلسه 1، 3402 کودک را آزمایش کردیم و در جلسه 2، زیر مجموعه ای از 920 کودک را مجدداً مشاهده کردیم (برای معیارهای انتخاب آنها به زیر مراجعه کنید). کودکان در جلسه 1 6 تا 10 ساله بودند (M = 8.41؛ SD = 1.17)، و در جلسه 2، اکنون 6 تا 11 سال سن داشتند (M = 9.25؛ SD = 1.1). در هر دو مقطع زمانی، تقسیم جنسیتی تقریباً برابر بود با 48.7٪ دختر در جلسه 1، و 51.0٪ در جلسه 2. کودکان از 22 مدرسه در شهرستان های جنوبی انگلستان، شامل 121 کلاس از سال تحصیلی 2-5.2 از زمان انتخاب انتخاب شدند. نرخ خروج بسیار پایین بود (1%)، این تقریباً کل بدنه دانشجویی تمام سال های هدف را نشان می داد. به عنوان شاخصی از ثروت/فقر (تیلور، 2018)، میانگین درصد وعده غذایی مدرسه رایگان در سطح مدرسه (FSM) 13.4٪ (محدوده 0.7-38.1٪) بود که میانگین ملی مدارس ابتدایی از همان دوره 14.1٪ بود ( وزارت آموزش و پرورش، 2017).

ما آزمایش کردیم، اما 22 کودک دیگر را حذف کردیم: 14 کودک تازه وارد بریتانیا شده بودند که به زبان انگلیسی تسلط کمی داشتند یا اصلاً مهارت نداشتند، 4 کودک کار را تمام نکردند، 1 کودک تاریخ تولد را نداشت و 3 نفر کدهای شناسایی درهم ریخته داشتند. مجوز اخلاقی برای همه مطالعات گزارش شده در اینجا توسط کمیته اخلاق تحقیقات علم و فناوری دانشگاه ساسکس اعطا شد.

مواد و رویه

کودکان به صورت حضوری و طی دو جلسه آزمایش مورد آزمایش قرار گرفتند. جلسه 1 بین اکتبر 2016 و آوریل 2017 برگزار شد و جلسه 2 7 تا 10 ماه بعد (M = 9.03 ماه؛ SD = 0.73) بین نوامبر 2017 و مارس 2018 برگزار شد. در اولین جلسه از فرزندان آنها در کلاس مورد آزمایش قرار گرفتند. با اندازه متوسط تقریباً 29 دانش آموز. شرکت کنندگان در هر زمان توسط سه محقق نظارت می شدند. در جلسه دوم، کودکان در اندازه های گروهی تقریباً 16 دانش آموز تحت نظارت حداقل دو محقق در هر زمان مورد آزمایش قرار گرفتند. در هر دو مورد، آزمایشها در مجموعهای از وظایف دیگر به عنوان بخشی از یک پروژه بزرگتر تعبیه شدند که نتایج آن در جای دیگری گزارش شده است (Simner, Smees, Rinaldi, & Carmichael, 2021؛ Smees, Rinaldi, & Simner, 2019). نمره یکی از این آزمونها در جلسه 1 – یک تکلیف یادگیری چندحسی برای پروژه دیگری – تعیین میکند که کدام کودکان در جلسه 2 مورد بازبینی مجدد قرار میگیرند (یعنی آنهایی که مجدداً مورد بررسی قرار گرفتند نمونهای از کودکان بودند که در یک چندحسی امتیاز کمتر از میانگین، متوسط و بالاتر از میانگین داشتند. کار یادگیری جفت کردن اعداد با حروف، که با مطالعه فعلی ارتباطی ندارد و به طور کامل در Rinaldi، Smees، Alvarez، و Simner، 2019 توضیح داده شده است. معیار هدف ما برای کودکان در زیر توضیح داده شده است.

آزمون جهت گیری خلاقیت کودکان: هنری (C-COT: ARTISTIC)

محرک های این آزمون 12 فعالیت است که به صورت تصاویر در 12 کارت جداگانه (5 cm × cm) نشان داده شده است. این فعالیتها با دقت انتخاب شدهاند تا نیمی از آنها در هنر خلاق باشند (به عنوان مثال، «نقاشی یا نقاشی بکش») و نیمی دیگر فعالیتهای غیر خلاقانه باشند (بهعنوان مثال، «به باشگاه باغبانی بپیوندید»؛ شکل 13 را ببینید). فعالیتهای خلاق سه حوزه (هنر، موسیقی و ادبیات) و فعالیتهای غیرخلاق (ورزش، سرگرمی و فضای باز) را شامل میشود. فعالیتهای خلاقانه ما از آیتمهای بهخوبی استفاده شده در ادبیات انتخاب شدهاند، و بهویژه، موارد خلاقانه منتخب ما از جمله مجموعههایی هستند که توسط یک گروه آزمایشی در Hocevar (1979) بهعنوان خلاقیت تجربی تأیید شد. هر یک از فعالیت های ما در یک خط سیاه و سفید نشان داده شده بود که با دقت توسط یک تصویرگر حرفه ای تهیه شده بود تا هر فعالیت را بدون ابهام به تصویر بکشد. برای هر فعالیت، ما مطمئن شدیم که دختران و پسران به تعداد مساوی شرکت میکنند. نمونه هایی از موارد ما در شکل 1 نشان داده شده است و مجموعه کامل کارت های فعالیت در ضمیمه A نشان داده شده است.

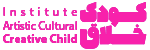

برای آزمایش، به هر کودک تخته تست مستطیلی خود داده شد، که ما 12 کارت فعالیت آنها را که به طور تصادفی از کودکی به کودک دیگر مرتب شده بود، روی آن قرار دادیم. در پایین هر لبه عمودی تخته، مکانگیرها شمارهگذاری شدهاند (1-6 در سمت چپ، 7-12 در حال اجرا در سمت راست، به شکل 2 مراجعه کنید). به کودکان گفته شد که تصور کنند به یک روز تفریحی میروند و فعالیتهایی برای انتخاب دارند که روی کارتهای 12 نشان داده شده است. به آنها دستور داده شد که فعالیتها را بر اساس میزانی که میخواهند انجام دهند، ترتیب دهند، یعنی فعالیت مورد علاقه خود را (“فعالیتی که بیشتر دوست دارید انجام دهید”) را روی کادر مشخص شده با شماره 1 قرار دهند. مورد علاقه بعدی آنها در شماره 2، و به همین ترتیب، تا کمترین مورد علاقه خود، که باید آن را در شماره 12 قرار دهند. برای کمک به این کار، کودکان می توانند تشویق شوند تا فعالیت هایی را که بیشتر دوست دارند انجام دهند به شش قسمت تقسیم کنند. و شش مورد را کمتر دوست دارند انجام دهند و سپس در هر یک از زیر مجموعه ها سفارش دهند. به کودکان دستور داده شد که هر کارت فعالیت را به موقعیت دلخواه خود (1-12) در لبههای تخته بر اساس ترجیح خود بلند کنند. برای اطمینان از اینکه کارتها در جای خود باقی میمانند، از یک چسب سبک استفاده شد (یعنی کارتهای ما دارای پشتی Velcro بودند، اگرچه این کار را میتوان روی یک سطح صاف بدون این کار تکرار کرد، یا صرفاً با مرتبسازی کارتها در یک توده مرتب شده). به بچه ها گفته شد که هیچ پاسخ درست یا غلطی وجود ندارد. زمانی که همه 12 جایگاهدار با 12 کارت فعالیت (از 1 تا 12) پوشانده شدند، این کار تکمیل شد. تکمیل این کار تقریباً 5 دقیقه طول کشید و آزمایش و دستورالعملهای کامل ما در ضمیمه A برای کاربران آینده ارائه شده است.پ

نتایج

طرح تحلیلی

در اینجا و در سراسر، تجزیه و تحلیل در SPSS 24.0 محاسبه شد. با تنظیم آلفا در p < .05 معمولی، و اصلاحات خانوادگی مربوطه در جایی که نشان داده شد اعمال می شود. تحلیلهای ما ابتدا بررسی میکنند که آیا جهتگیری خلاق (C-COT: امتیاز هنری) یک ویژگی پایدار در طول زمان است، بر اساس 920 کودک که در دو نوبت (جلسات 1 و 2) در آزمون شرکت کردند. ما یک همبستگی را در دو جلسه انجام دادیم، سپس در هر گروه به طور جداگانه تکرار کردیم (تصحیح برای مقایسه های چندگانه). در مرحله بعد، در نظر می گیریم که آیا جهت گیری خلاق، تأثیرات جمعیت شناختی (به عنوان مثال، جنسیت، سن) را بر اساس N 3402 کودک در جلسه 1 نشان می دهد یا خیر. در اینجا، ما یک مدل رگرسیون چندگانه با اثرات مختلط را اجرا کردیم که متغیرهای جنسیت و سن را به عنوان متغیرهای کمکی ثابت وارد می کند و مدل سازی می کند. تغییرات تصادفی در سطح مدرسه و کلاس درس (پرسیدن اینکه آیا برخی از گروه های کلاس خلاقیت بیشتری دارند، شاید به سبک تدریس مربوط باشد). مدل تهی ما (مدل 1) تغییرات خام را در C-COT نشان میدهد: نمرات هنری در بین کودکان و مدرسه/کلاس درس، در حالی که مدلهای 2 و 3 به ترتیب جنسیت/سن و عبارت تعامل را به تدریج اضافه میکنند. در نهایت، با مقایسه کودکان آزمایش شده در پاییز و بهار با استفاده از آزمون t، اثرات محیطی را ابتدا به تأثیرات فصلی بر جهت گیری خلاق ارزیابی می کنیم. در نهایت، ما تأثیرات اجتماعی-اقتصادی بر جهت گیری خلاق را با اجرای یک همبستگی بین C-COT در سطح مدرسه بررسی کردیم: نمرات هنری، و معیار اجتماعی-اقتصادی مدرسه (درصد FSM؛ یعنی درصد مدرسه واجد شرایط برای وعده های غذایی رایگان مدرسه) .

ثبات جهت گیری خلاق در طول زمان

برای کدگذاری آزمون جهت گیری خلاق (C-COT: Artistic)، به هر یک از شش فعالیت خلاقانه (مثلاً “نقاشی یا نقاشی”) امتیازی از 1 تا 12 بسته به رتبه بندی ترجیحی کودک اختصاص دادیم. اگر کودک آن را انتخاب کرده بود 1 (بیشترین ارجحیت)، آن را 12 امتیاز. به گزینه 2 11 امتیاز، 3 10 امتیاز و غیره. سپس نمرات در تمام شش فعالیت خلاقانه برای هر کودک جمع شد و با تفریق 21 امتیاز نهایی محاسبه شد (یعنی کمترین امتیاز ممکن، اگر هر شش مورد خلاق در آخر قرار می گرفتند). این تفریق یک امتیاز نهایی بصری برای هر کودک در محدوده 0-36 ایجاد می کند، جایی که نمرات بالاتر با جهت گیری خلاقانه تر مطابقت دارد.

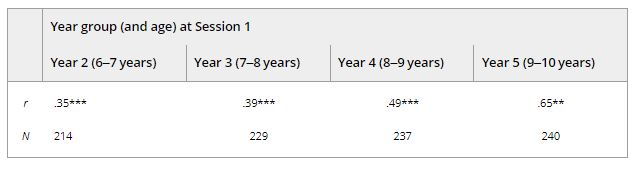

ما ابتدا C-COT: نمرات هنری را برای هر کودک که در دو جلسه ترسیم شده مقایسه کردیم. مقایسه نمرات به این روش نشان می دهد که پایایی آزمون-آزمون مجدد بسیار معنادار است (r = .48، p < .001، n = 920) و در اندازه اثر متوسط (با استفاده از قراردادهای اندازه اثر در اینجا و در سراسر کوهن، 1988). با این حال، به شدت با سن کودک، با قوی ترین اندازه اثر برای کودکان 9-10 ساله (r = .65، p < .001؛ جدول 1 را ببینید) اما هنوز اثرات متوسط حتی برای کوچکترین کودکان ما داشت. 6-7 ساله (r = .35، p < .001). این یافتهها نشان میدهد که ویژگی جهتگیری خلاق در طول زمان، حتی در گزارش خود از کودکان 6 ساله پایدار است، اما با افزایش سن پایدارتر میشود.

جدول 1. همبستگی های پیرسون (r) برای C-COT: نمرات هنری در دو نقطه زمانی (جلسه 1 و جلسه 2) که تقریباً 9 ماه از هم جدا شده اند. نتایج بر اساس سال تحصیلی (و سنین مربوطه) با اندازههای گروه نشان داده شده (N) تقسیم میشوند. تکرار تحلیلهای ما با استفاده از همبستگیهای درون کلاسی، الگوی یکسانی از نتایج را نشان داد

بررسی سطح کودک و اثرات محیطی

ما تحقیقات خود را با در نظر گرفتن اینکه آیا تفاوتهای فردی در جهتگیری خلاق از کودک به کودک را میتوان بر اساس سن، جنسیت و محیط (مثلاً تأثیر مدرسه) دنبال کردیم. Creemers و Kyriakides (2010) پیشنهاد می کنند که تأثیرات مدرسه در طبیعت چند سطحی است و در چهار سطح قرار دارد: دانش آموز، کلاس درس، مدرسه و سیستم. مدلسازی اثرات آموزشی همچنین تخمینهای مطمئنتری از تأثیرات ثابت یا مستقل ارائه میدهد (فیلد، 2013). تکنیکهای رگرسیون خطی سلسله مراتبی مناسبترین روشها برای ارزیابی اثرات مدرسه/کلاس هستند، اگر تعداد گروههای سطح بالاتر به اندازه کافی زیاد باشد (Opdenakker & Van Damme, 2000; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002؛ Snijders & Bosker, 1999). از آنجایی که مجموعه داده های خودمان بزرگ و در واقع سلسله مراتبی بود (کودکان [سطح 1] درون کلاس ها [سطح 2] و کلاس ها تودرتو در مدارس [سطح 3])، ما تجزیه و تحلیل رگرسیون چند سطحی را با استفاده از دستور اثرات مختلط در SPSS 24.0 انجام دادیم. ) وارد کردن سن و جنسیت به عنوان متغیرهای کمکی ثابت.

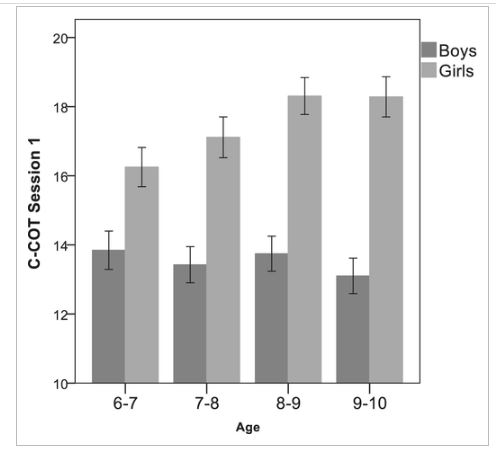

جدول 2 میانگین خام C-COT را نشان می دهد: نمرات هنری (جهت گیری خلاق) برای دختران و پسران در جلسه 1 (یعنی بزرگترین اندازه گروه؛ n = 3402)، و شکل 3 تفاوت های مربوط به سن را در هر جنسیت، قبل از این نشان می دهد. مدل سازی داده ها به صورت سلسله مراتبی

جدول 2. آمار توصیفی برای C-COT: هنری (جلسه 1)

شکل 3

در نمایشگر شکل باز کنید

پاورپوینت

میانگین نمرات برای C-COT: هنری (جهت گیری خلاق) در پسران و دختران در تمام سنین. نوارهای خطا 95% فواصل اطمینان را نشان می دهند.

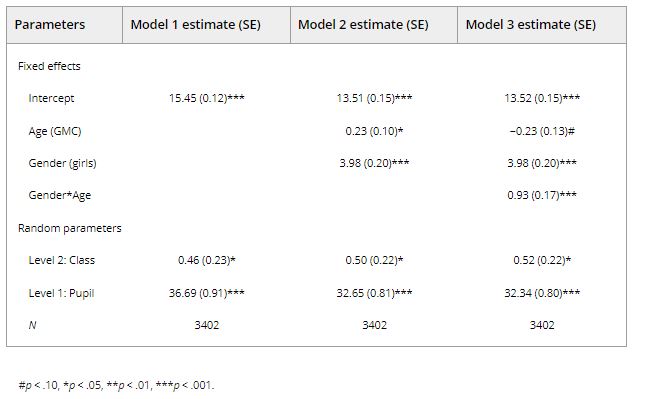

مدل 1 (جدول 3) مدل چندسطحی تهی را قبل از وارد کردن پیشبینیکنندههای فرزند نشان میدهد. فقط کلاس درس به عنوان یک سطح سازمانی تصادفی در نظر گرفته شد، زیرا تنوع مدرسه معنیدار نبود، بنابراین از مدل سه سطح اولیه (Est. = 0.07، SE = 0.12، p = .573 حذف شد). در مدل 2، جنسیت و سن هر دو پیشبینیکنندههای قابل توجهی برای جهتگیری خلاق بودند، به طوری که دختران و کودکان بزرگتر نسبت به پسران و کودکان کوچکتر به خلاقیت گرایش داشتند (مدل 2: تخمین دختران = 98/3، p < .001؛ تخمین سنی = 23/0، p < .05). علاوه بر این، یک تعامل معنیدار بین جنسیت و سن وجود داشت (مدل 3: برآورد = 0.93، p < .001). این را می توان در شکل 3 مشاهده کرد، که نشان می دهد ارتباط بین سن و C-COT: نمره هنری برای دختران قوی تر است (یعنی جهت گیری خلاقانه دختران با افزایش سن به شدت افزایش می یابد). همین رابطه برای پسران در آلفای مرسوم به اهمیت نمی رسد (مدل 3: تخمینی = 0.23-، p = .071؛ جدول 3 را ببینید) اما روند منفی داشت (یعنی، بر خلاف دختران، پسران با گرایش خلاقانه تر نمی شوند. سن، اما روند معکوس). در نهایت، پس از در نظر گرفتن جنسیت و سن، نسبت کوچک اما قابل توجهی از واریانس با تفاوت های محیطی توضیح داده شد. اگرچه هیچ تفاوتی در سطح مدرسه در نمرات جهت گیری خلاق وجود نداشت، اثرات قابل توجهی در سطح کلاس وجود داشت (همبستگی درون کلاسی [ICC] = 0.016؛ مدل 2، جدول 3، ردیف 4 ستون 4) که نشان می دهد جهت گیری کودکان به سمت فعالیت های خلاقانه می تواند به طور قابل توجهی بین همکلاسی های خود به اشتراک گذاشته شود.

جدول 3. مدل های چند سطحی که تأثیرات ثابتی بر جهت گیری خلاق را شناسایی می کنند (C-COT: هنری، جلسه 1). سن (متوسط بزرگ، GMC) نشان دهنده سن کودک در جلسه 1 است. برآورد ضریب مدل با خطای استاندارد (SE) در پرانتز است. جدول تخمین C-COT را نشان می دهد: نمرات هنری برای دختران (در مقایسه با پسران). جنسیت*سن اعتدال بین جنسیت و سن است

ما با در نظر گرفتن دو اثر نهایی زیست محیطی به پایان رسیدیم. اولین مورد به این واقعیت مربوط می شود که کودکان در جلسه 1 در هر دو ترم پاییز (اکتبر-دسامبر) یا ترم بهار (ژانویه-آوریل) مورد آزمایش قرار گرفتند. این امکان وجود دارد که میانگین نور روزانه خورشید بر جهت گیری خلاقانه تأثیر بگذارد (به Kombeiz and Steidle (2018) برای تأثیر نور بر خلاقیت مراجعه کنید). با این حال، ما تفاوتی در C-COT پیدا نکردیم: نمرات هنری برای کودکانی که آزمون را در پاییز (M = 15.32، SD = 5.97) یا بهار (M = 15.53، SD = 6.17)، t(3490 = ) ، p = .330. در نهایت، با مقایسه C-COT: نمرات جهت گیری خلاق هنری در برابر درصد FSM (غذاهای رایگان مدرسه) هر مدرسه، محیط اجتماعی-اقتصادی را در نظر گرفتیم. همانطور که در بالا ذکر شد، FSM متغیر سطح مدرسه است که به عنوان شاخص ثروت/فقر در ناحیه مدرسه (تیلور، 2018) در نظر گرفته شده است و مدارس ما در وضعیت FSM از 0.7٪ تا 38.1٪ (میانگین ملی 14.1٪) قرار داشتند. با این حال، ما هیچ رابطه معناداری بین FSM هر مدرسه و میانگین C-COT آن: نمره هنری (در جلسه 1) پیدا نکردیم. این اطلاعات مهمی را نشان میدهد که به نظر نمیرسد جهتگیری خلاق تحتتاثیر سطوح فقر در ناحیه هر مدرسه قرار داشته باشد (r = .09، p = .706).

بحث

داده های ما نشان می دهد که ویژگی جهت گیری خلاق در طول زمان پایدار است. این حتی در گزارش خود از کودکان 6 ساله نیز صادق بود، اما با افزایش سن هنوز پایدارتر می شود (اندازه اثر متوسط در 6 تا 7 سال و بزرگ در 9 تا 10 سال). جنسیت و سن هر دو پیشبینیکنندههای قابل توجهی برای جهتگیری خلاق بودند، به طوری که دختران و کودکان بزرگتر نسبت به پسران و کودکان کوچکتر به خلاقیت گرایش داشتند. ما همچنین یک تعامل بین سن و جنسیت پیدا کردیم، که نشان میدهد جهتگیری خلاقانه برای دختران در طول زمان به طور معنیداری افزایش مییابد، اما برای پسران نه (و پسران حتی در جهت معکوس گرایش دارند). در نهایت، ما یک اثر محیطی قابلتوجهی را در سطح کلاس پیدا کردیم، که نشان میدهد جهتگیری کودکان به سمت فعالیتهای هنری خلاقانه در بین همکلاسیهایشان به طور قابل توجهی به اشتراک گذاشته میشود. با این حال، ما هیچ رابطه ای بین جهت گیری خلاق و متغیر اجتماعی-اقتصادی خود (سطوح فقر در منطقه مدرسه) پیدا نکردیم، و هیچ تفاوتی در جهت گیری خلاق برای کودکانی که در پاییز در مقابل بهار شرکت می کنند، نیافتیم. بنابراین نتیجه می گیریم که آزمون ما به خودی خود با زمان سال گیج نمی شود و به همین ترتیب، جهت گیری خلاقانه کودکان با فصل تغییر نمی کند.

مطالعه 2: آیا جهت گیری خلاق با تفکر واگرا، شخصیت خلاق و/یا مشارکت خلاق مرتبط است؟

مواد و روش ها

شرکت کنندگان

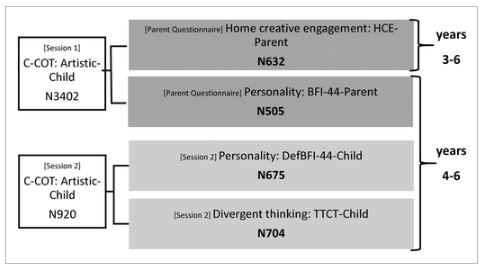

در این مطالعه، ما دو گروه را مورد آزمایش قرار دادیم: والدین و فرزندان. برای کمک به خواننده، شکل 4 یک کمک بصری برای درک نمونه های شرکت کننده ما ارائه می دهد.

Our child sample was a subset of the 920 children tested in Session 2 above, specifically, those children who were 8+ years (i.e., old enough for our measures of personality and divergent thinking; see below). Practically speaking, these were the Session 2 children who were in Years 4–6 (and Years 3–5 when first recruited for Session 1). These comprised 675 children for our self-report personality test (n = 675, mean age = 9.69; SD = 0.88; 52.6% girls) and 704 children for our divergent thinking test (n = 704, M = 9.73; SD = 0.88; 52.7% girls). All children entered this study with their C-COT: Artistic back-data from Study 1, and all testing took place contemporaneously with Session 2 (see Study 1).

We also tested 709 parents, whose children had taken part in Session 1 of Study 1. Their children were 6–12 years5 (M = 9.00; SD = 1.31; 46.5% girls) at the time of their parent’s testing. These 709 parents had responded to a recruitment drive in which we targeted all parents of our child cohort from Study 1. Those parents who responded became our testing sample, comprising 19% of the entire parent body. These was a representative sample: Their children were no different in age (responders: M = 8.41, SD 1.18; non-responders: M = 8.40, SD 1.16; t(3400) =0.248, p = .804), no different in gender (responders = 47% girls; non-responders = 49%; X2 (1, N = 3402) = 0.55, p = 195), and, crucially, no different in their C-COT: Artistic creative orientation scores (responders: M = 15.53, SD = 6.31; non-responders: M = 15.48, SD = 6.04 terms; t(3400) = 0.521, p = .602).

From our 709 parent respondents, 632 provided data related to their child’s home learning environment (M = 9.00; SD = 1.31; 46.2% girls) and 505 provided their child’s personality data (M = 9.55; SD = 0.96; 45.3% girls), which was slightly fewer since only children 8+ years and older were included in the latter analysis (see below). For clarity, we point out that our 709 parents partially overlapped with the children for whom we had data from Study 1 of Session 2, but fully overlapped with those children from Study 1 of Session 1. An overview of parent and child participants for this study is shown in Figure 4, which shows our overall test design, and participants within each measure.

MATERIALS AND PROCEDURE

Parent testing

Our parents were sent a questionnaire in October 2017, followed by a reminder approximately 8 months later. Parents completed their questionnaire either electronically (n = 564) using an online testing platform (Qualtrics Provo, 2015) or in a pencil-and-paper version (n = 145). This decision was dictated by whether participating schools contacted their parent body electronically or with paper letters. All tests were presented identically whether electronic or paper, and have been validated across both these formats (Rinaldi et al., 2020). Embedded within this questionnaire were two measures of interest for the current study, which we describe below (with other measures to be reported elsewhere).

Parent-rated personality: BFI-44-Parent (available from the Berkeley Personality laboratory (https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~johnlab/measures.htm); see John et al., 1991, 2008; John & Srivastava, 1999). The BFI-44-Parent is a 44-item personality questionnaire. Each item begins with the phrase “I see my child as someone who is…” followed by the description of a personality trait (e.g., Item 22 is “I see my child as someone who is generally trusting”). Parents were asked to indicate how much they equate each statement with their child using a 5-point Likert scale (disagree strongly, disagree a little, neither agree nor disagree, agree a little, and agree strongly). This questionnaire returns five scores (see Results), one for each of the “Big Five” personality traits of openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. There were 10 ten items for openness, nine for conscientiousness, and eight for extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. Our interests here were for the trait of Openness to Experience, which has been found to predict creativity in adults (Batey & Furnham, 2006; Silvia, Nusbaum, Berg, Martin, & O’Connor, 2009; Soto & John, 2009). Although this dimension has been less coherent in children (Measelle, John, Ablow, Cowan, & Cowan, 2005; Resing, Bleichrodt, & Dekker, 1999), it arises as a separate factor with subdomains at around 8 years (Mervielde, Buyst, & De Fruyt, 1995). It was for this reason that we examined personality of our cohort aged 8 and above (either child-rated or parent-rated). The measure took between 5 and 10 minutes to complete.

Home creative engagement questionnaire: Parents were given a questionnaire about home environment and activities, using items previously developed for primary-aged children from the Effective Pre-school, Primary and Secondary Education Project (Sylva et al., 2008). Within this 20-item task were two questions where parents estimated how often their child performed two different sets of creative activities on their own in the home (1 = paint, draw, make models; 2 = enjoy dance, movement, music). Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale (never, hardly ever, occasionally, 1 or 3 times a week, and every day), and each of the two sets of creative activities was rated separately. These two items appeared among other family-oriented questions probing home environment (e.g., highest household qualification, parent–child engagement) and other household factors (e.g., birth order), to be reported elsewhere.

Child testing

We remind the reader that data for this study were elicited during Session 2 of our testing sweep described in Study 1. As before, tests were embedded in a series of other tasks as part of a larger project, whose results are to be reported elsewhere. For our current purposes, our target measures are described below (and Figure 4 summarizes which tests were presented to each participant group).

Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) Verbal Form A—Unusual Uses (Torrance, 2008). This task measures creative (divergent) thinking by asking children to generate as many answers as possible to a single question requiring creative thought. Although the link between divergent thinking and creative interests is usually modest (Clapham, 2004; Zeng, Proctor, & Salvendy, 2011), divergent thinking is generally higher in creative people (Runco, 1987) and divergent thinking skills in childhood predict creative achievement, concurrently and in later life (Runco, Millar, Acar, Cramond, 2010b; Runco, 1992). In our study, children were first told they were going to have the opportunity to use their imagination and were asked to think of as many interesting and unusual uses of a cardboard box. Children were told that there were no right or wrong answers, and they could be thinking of one box or many. They provided their answers on a written response sheet containing 50 lines, and were given 10 minutes to complete the task.

Child-rated personality: Def BFI-44-C (Rinaldi et al., 2020). The Def BFI-44-C is a 44-item Likert-style self-report personality questionnaire, suitable for children from age 8 years. This questionnaire is identical to the parent-report personality questionnaire described above, except for the following. Items now begin with the phrase “I see myself as someone who…” (e.g., Item 22 is “I see myself as someone who is generally trusting”). Measures of child-reported personality (and related theories; Mervielde et al., 1995) suit children 8+ years, hence the age of our child participants in this study. This child version provides age-appropriate definitions for 14 vocabulary items, so they are understandable to even the youngest children (e.g., in the item “I see myself as someone who generates a lot of enthusiasm,” the final word is defined as “This means getting excited about things”; see Rinaldi et al., 2020). This adaptation was validated by Rinaldi and colleagues (Rinaldi et al., 2020) and was based originally on adult/ adolescent versions of the BFI-44 (John et al., 1991, 2008; Soto et al., 2008). Cronbach’s alphas show moderate reliability for all components (openness, α = .68; conscientiousness, α = .70; extraversion, α = .66; agreeableness, α = .73; and neuroticism, α = .68), and the instrument has concurrent validity in a number of ways (e.g., neuroticism positively correlates with children’s anxiety at r = .41, using the SCARED questionnaire; Birmaher, En, Balach, & Neer, 1997; Birmaher et al., 1999).

We administered the questionnaire to children using touchscreen electronic tablets, where definitions appeared as screen pop-ups. Children were given the following instructions “You’re going to read some sentences that might describe you, or they might not. For example ‘I see myself as someone who is bossy.’ Is this true about you?” Each item was placed adjacent to on-screen response buttons displaying the Likert labels (from left to right: strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, and strongly agree). The responses were explained to the children, and they were shown how to click for a definition if they did not understand a word. Children completed the Def BFI-44-C in approximately 10 minutes.

RESULTS

Analytic plan

Our analyses examine whether children’s creative orientation data (taken from the C-COT: Artistic described in Study 1) show relationships with personality (child-completed, parent-completed), divergent thinking (child-completed), and home creative engagement (parent-completed). For our child-completed measures, we compared scores elicited within the same session (i.e., using C-COT: Artistic from Session 2). We ran one correlation on children’s data for creative orientation (C-COT: Artistic) and the personality trait of openness, then repeated our correlation for each of the two subfacets of this trait (openness to aesthetics and openness to ideas; see below) correcting for familywise multiple comparisons. Alongside, we ran parallel analyses on the equivalent parent data, correcting again for multiple comparisons. For parent-completed measures (which were not tied to any particular session), we compared with C-COT: Artistic scores from Session 1, because this included the largest number of C-COT: Artistic participants. Next, we compared creative orientation (C-COT: Artistic scores) against our measure of divergent thinking using the coding described below, running a single correlation for the entire group of children, and then dividing the children into two groups (see below), running a correlation on each subgroup and correcting for multiple comparisons. We ran a final correlation to compare creative orientation (C-COT: Artistic) scores against home creative engagement.

Personality: Openness to experiences: For both the child-rated measure (Def BFI-44-C) and parent-rated measure (BFI-44-Parent), the response to each item was scored 1–5, from disagree strongly to agree strongly, with reverse-coding where appropriate (i.e., where traits were negatively expressed; e.g., conscientiousness; “I see myself as someone who can be somewhat careless”). Scores were then averaged within each trait, to produce a score for each of the five personality dimensions (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism). Scores from the (child-rated) Def BFI-44-C were ipsatized to account for acquiescence in responding (following Rinaldi et al., 2020). Our interests here were for the trait of openness to experience, which has been found to predict creativity in adults (Batey & Furnham, 2006; Silvia et al., 2009; Soto & John, 2009). We found a significant association between C-COT: Artistic scores (in Session 2) and the factor of openness, which was medium in child’s ratings (r = .30, p < .001, n = 675) and smaller in parent’s rating (r = .23, p < .001, n = 505).

However, the factor of openness to experience can also be analyzed as two separate facets: openness to aesthetics and openness to ideas (see for details of items; Soto & John, 2009). The former facet is particularly of interest, given that our measure investigates artistic inclination (Kaufman et al., 2016). As predicted, we found a significant association between C-COT: Artistic scores and the aesthetics facet, with a medium effect size (child’s rating: r = .34, p < .001, n = 675; parent’s rating r = .33, p < .001, n = 505), and indeed a weaker relationship with the ideas facet (child’s rating: r = .17, p < .001, n = 675; parent’s rating r = .13, p < .01, n = 505), with p values corrected for multiple comparisons.

Divergent thinking: In this analysis, we compared divergent thinking scores (from the TTCT) against creative orientation (from the C-COT: Artistic). For the divergent thinking task (uses of a cardboard box; TTCT), answers were scored on fluency (the number of legitimate ideas produced) and flexibility (number of different types of ideas produced). For fluency, any viable idea (i.e., not nonsense) received a single fluency point, and a child’s total fluency score equaled the sum of all viable ideas produced. Flexibility was calculated as the number of different categories of ideas the child had used (e.g., household items; buildings; transport). For example, if a child had listed 10 ideas, five types of building, and five different household items, they would receive a fluency score of 10 and a flexibility score of 2. Possible categories were taken from Torrance (Torrance, 2008) who provided 28 different category types in total. A second coder verified all codings, and any disagreements not resolved by discussion were sent to the publisher of the TTCT (Scholastic Testing Service Inc.) for a final coding decision. In line with others (Mouchiroud & Lubart, 2001), we chose not to use the third score originality due to unreliability concerns (e.g., Kim, 2006). Specifically, many of the objects mentioned by our child participants in 2017–18 would have been classed as “original” simply because they were not in existence when the manual was written in 2008 (e.g., electronic tablets). This problematic aspect of originality scoring has been raised by others (e.g., Kim, 2006, who noted that “originality scores also would change among various demographics over time [so I] question the credibility of originality scores from 1998, which used the same lists as in 1984.” p. 10).6

Across the entire sample (age 8–11 years at Session 2), we failed to find an association between C-COT: Artistic creative orientation and divergent thinking (fluency r = −0.03, p = .371; flexibility r = .02, p = .533, n = 704). However, we reasoned that although children not gifted in divergent thinking may still wish to engage (paint, draw etc.), those who are gifted may absolutely wish to engage. In other words, we reasoned that there may be a relationship to C-COT: Artistic for children with higher divergent thinking skills. We therefore took the highest scoring children in the divergent thinking test and examined whether they showed a relationship between divergent thinking and creative orientation (C-COT: Artistic). To do this, we selected the top 25% performers in one domain of divergent thinking (fluency, the most commonly used metric) and examined whether the other domain (flexibility) mapped onto creative orientation. (In other words, we kept one element of divergent thinking constant, while exploring the other.) We found a significant relationship between children’s flexibility and C-COT: Artistic scores within this high-performing group (r = .24, p < .001, n = 704; p-value-corrected). This suggests that for children who are fluent in creative ideas, they are more drawn to creative activities as their creative flexibility increases. This relationship can be seen in Figure 5.

Home creative engagement questionnaire: parents: Parents described the frequency with which their child performed two sets of creative activities on their own at home (paint, draw, make models and enjoy dance, movement, and music). We scored each set of response 1–5 (never, hardly ever, occasionally, 1 or 2 times a week, and every day) and then averaged these two scores to give each child an overall creative engagement score. There was a significant association with creative orientation (with a small effect size, r = 0.27, p < .001, n = 632), suggesting that children’s orientation toward creative activities in the C-COT: Artistic also related to the amount of time they spent engaged in creative activities at home.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that children’s self-reports about their creative orientation matched to a creative personality type (openness to experiences), as elicited from both children and parents. Within this trait, we explored both subfacets (openness to aesthetics and openness to ideas; Soto & John, 2009) and found, as expected, a stronger relationship with the former than the latter (since openness to aesthetics is the subfacet particularly linked with artistic inclination; Kaufman et al., 2016). We also found that creative children’s orientation toward creative activities in the C-COT: Artistic related to the amount of time they spent engaged in creative activities at home.

We failed to find an association between creative orientation and divergent thinking in our overall sample (i.e., fluency and flexibility in their uses for a cardboard box). This suggested that children can enjoy and seek out painting, drama, and music even if they have no superior divergent thinking abilities. Nonetheless, when looking at children with the very highest divergent thinking skills (i.e., top 25% most fluent children), we found that creative orientation did relate to divergent thinking skills (i.e., keeping one element of divergent thinking constant [fluency], while exploring the other [flexibility]). This finding tells us that children who are fluent in creative ideas are more drawn to creative activities as their creative flexibility increases. Our null result (groupwise) and significant result (in the top quartile) paint an interesting picture. They show that children largely wish to engage in creative activities whether they are gifted in divergent thinking or not. Yet importantly, those who are gifted absolutely wish to engage, all the more so as their flexible thinking increases.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Our novel measure of creative orientation, the C-COT: Artistic, assesses children’s preferences for creative artistic activities (Amabile, 1983; Kaufman, 2013; Runco, 1996) and aptly captures how much children would like to engage in creative artistic activities (whether they routinely do in daily life or not). This avoids the bias arising from differing home backgrounds with their socio-economic and motivational differences, all of which could influence creative engagement according to different levels of parental resources and drive. We first showed that creative orientation as measured by the C-COT: Artistic is an enduring trait, with significant reliability across test and retest, over approximately 9 months. Unsurprisingly, although still significant and moderate, the effect size was smallest for the very youngest children (6–7 years, r = .35) but more robust for children aged 9–10 years (r = .65). Changeable interests at younger ages have been found elsewhere (Tracey, 2002; Tracey & Ward, 1998; Wigfield & Eccles, 1994) and our instrument holds up very well against earlier findings. For example, Tracey (Tracey, 2002) generated a comparable score by eliciting children’s “liking” ratings for 5 artistic activities (e.g., drawing; using a 5-point scale from do not like at all, to like a lot). “Liking” measurements have a long history in creativity research (e.g., Helson, 1966), and Tracey’s measurements were taken as part of the Inventory of Children’s Activities (ICA), which assesses 6 different types of interest (e.g., Artistic interests, Social interests; Holland, 1973, 1985). As found here, the stability of artistic interests over 1 year was greater for their older children (middle school, age 12–13 years, r = .72) than for their younger children (elementary school, age 10–11 years, r = .46). Importantly, our own measure appears to be more robust over time than the ICA, given a comparison where our age-groups coincide (i.e., our stability for 9- to 10-year-olds over approximately 9 months was r = .65 compared to r = .46 for the ICA). Indeed, our long-term retest over 9 months showed robustness that was similar or greater to a retest of the ICA conducted over just 1 week (Tracey & Ward, 1998; 9- to 10-year-olds tested over 1 weeks, r = .58; and our own 9- to 10-year-olds over approximately 9 months, r = .65). Our measure therefore performs particularly well over extended time periods, while also showing known age-related differences.

We also found demographic and environmental influences. Creative arts orientation was higher for girls than for boys, and a similar finding emerged in previous “liking” judgments for creative activities (e.g., Tracey, 2002). Similar gender differences are also found in other aspects of creative thinking, and creative engagements and activities (Runco, Cramond, Pagnani, 2010a; Baer & Kaufman, 2008; Chan, 2005; Runco, 1986), as well as in openness to experiences (Weisberg, DeYoung, & Hirsh, 2011) although findings are sometimes mixed. We also found that age interacted with gender, because creative orientation increased with age for girls, but not boys—and these latter showed a numerical trend in the opposite direction (approaching significance, p = .07). This finding is likely to reflect a broader gender effect, widely noted elsewhere. For example, arts participation by girls (e.g., theater, drama, music, literature) already outstrips boys by school entry, and can be further seen in academic choices they make in later schooling (Blood, Lomas, & Robinson, 2016). Such differences reflect changes in interests (Hilton & Berglund, 1974; Tracey, 2002; Tracey & Ward, 1998; Weinburgh, 1995) and may in turn relate to differences in how the genders perceive their competence in different domains (Bian, Leslie, & Cimpian, 2017; Marsh & Yeung, 1998; Tracey, 2002; Tracey & Ward, 1998). It should be noted, however, that preferences for particular activities may reflect motivations other than creative expression, such as those related to emotion regulation (Drake & Winner, 2013), as well as the perceived difficulty or value of artistic subjects in schools (McPherson & O’Neill, 2010). However, our study shows for the first time that gender effects are apparent for creative arts activities even where children are given the most opportunity to freely indicate their creative orientation, unrelated to parental influences, and these are apparent from the very youngest ages.

We also found a significant effect of school class, although it was very small (approximately 2% of the variance in C-COT: Artistic scores was attributable to the class). This was notably smaller than 5–10% typical of class effects in cognition/academic attainment, but very much in line with smaller effects typical of psychological well-being and social behavior (Crawford & Benton, 2017; Sammons et al., 2008). We point out that the variation found between classes was within our English schooling system and that class/school effects can vary markedly from country to country (OECD, 2004). Finally, we found no evidence of other environmental influences: Children were no more creatively orientated from one season to the next, and there no was effect of their school’s socio-economic environment, as measured by the percentage FSM metric (i.e., of free school meals for children within each school).

Next, we considered whether creative orientation was linked to other traits of personality and cognition. In doing so, we also tested whether our C-COT: Artistic instrument converges with related tools. Although domains of creativity have weaker associations among them than domains of, say, cognition (Lunke & Meier, 2016; Plucker & Runco, 1998; Runco, 1987), we nonetheless found associations between the C-COT: Artistic and other creativity measures (we tested openness to experience, divergent thinking, and home creative engagement). Hence, the C-COT: Artistic predicted both openness to experiences and engagement in creative activities at home, with moderate associations (rs = .3). When openness to experiences was split into its two component facets (aesthetics and ideas), both were significantly related to C-COT: artistic scores, but aesthetics had the stronger relationship (r = .34 vs. r = .17). This is to be expected given the aesthetics facet is concerned primarily with interest in the creative arts. Our findings also suggest that traits measured by the ideas facet (i.e., children’s ability to generate ideas, be curious, and have wide interests) are more distinct from creative orientation.

The C-COT: Artistic did not predict divergent thinking skills for the entire group aged 6–10 years. This suggests that children can wish to seek out painting, drama, and music whether they have superior divergent thinking abilities or not. This finding is in line with the lower association we found between C-COT: Artistic and the ideas subfacet discussed above (i.e., creative orientation has only a remote association with a creative facet linked to ideas). Furthermore, it also patterns with a recent study, which, like us, elicited from children fluency scores using our divergent thinking task (the TTCT; requiring multiple uses for an object; Okuda, Runco, & Berger, 1991). Okunda and colleagues found no significant groupwise association between fluency and a measure of how many times children performed creative activities in the past (i.e., a task of creative engagement, which are used as a proxy in the adult literature for creative orientation—although see Introduction for the limitations on this in children). Together, our findings support previous research suggesting that domains of creativity sometimes have relatively weak associations among them (Lunke & Meier, 2016; Plucker & Runco, 1998; Runco, 1987).

We did find a significant relationship between C-COT: Artistic and divergent thinking for a subset of our participants, and these were children excelling in divergent thinking. Hence, the top 25% of children within (the fluency dimension of) our divergent thinking task showed a relationship between creative orientation and the flexibility of their divergent thinking. In other words, children who are gifted in divergent thinking become more driven to engage in creative activities as their creative flexibility increases. A close parallel to this finding can be seen in the field of cognition, where a parallel trait to creative orientation is called “Need for Cognition” (i.e., whereas creative orientation is one’s intrinsic motivation to engage in creative pursuits, Need for Cognition is one’s intrinsic motivation to engage in cognitive pursuits; Cacioppo & Petty, 1982). Crucially, Need for Cognition requires a minimum amount of cognitive expertise (in working memory capacity) to show any relationship with cognitive thinking (Hill, Foster, Sofko, Elliott, & Shelton, 2016). Here, we see a parallel finding: that creative orientation may require a minimum amount of creative expertise to see any relationship with creative thinking. It is important to recognize, however, that our approach was exploratory and should therefore be considered only a preliminary early suggestion. Future studies would benefit from replicating our findings more directly before we could conclude with confidence that flexible thinking relates to creative orientation, for children who already think creatively.

Finally, we found a small but significant relationship between creative orientation (C-COT: Artistic) and the time spent engaged in creative activities in the home. To some extent, it is not surprising that children would choose to do activities on a fictional fun day that they also complete at home—assuming this latter has at least some degree of free choice. However, whereas home activities may be restricted by parental influences or home resources (not all home have clay for modeling, for example), the C-COT: Artistic paradigm allows children greater freedom to express their creative arts orientation, in ways that home or other engagement metrics cannot (see Introduction).

In summary, we have investigated children’s creative orientation while also validating a novel measure of creative orientation for children as young as 6 years old. Our test is fast and easy to administer, and it provides a measure of creativity that is complementary to existing instruments (e.g., personality instruments) while adding a novel dimension hitherto under-explored. Children reported during our study that they enjoyed completing the task, and they did so quickly (within 5 minutes; see Methods). They also completed our task without requiring support from researchers, and we were able to administer the task meaningfully within large cohorts (we were able to screen entire classes together). Our measure avoids the confounds associated with eliciting creative engagements, which although successful in adults, falls short when testing children. Understanding children’s creative orientations gives especially valuable insight into their individual dispositions and sources of pleasure. It might also provide pathways to well-being if their creative orientations can be revealed through testing, and then matched with an opportunity to enact them. We present our complete C-COT: Artistic task in the Supplementary material, and encourage researchers to use our measure when researching the children’s creative orientation.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

We declare no financial interest in conducting this research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RS, JS, TM, DC, and LR designed the study. RS interpreted the results and ran the data analysis. RS and JS wrote the manuscript. RS, DA, and LR carried out the data collection.

Appendix A: Children’s Creative Orientation Test: Artistic (C-COT: Artistic)

Below are the 12 of our test (first six = creative; second six = non-creative). Activities must be printed onto 12 individual cards (5.0 cm × 8.0 cm) and laid out randomly on a testing board (29.5 cm × 42.0 cm; see Figure 1). The instructions given to children are as follows:Imagine you are going on a fun day out, and these are the activities you could choose from. Put your favorite activity (the activity you would like to do the most) on number 1; your next favorite on number 2, your next favorite on 3, and so on, all the way down to your least favorite which goes on number 12. So you are ordering them by how much you would like to do them. There are no right or wrong answers, just place them wherever you think best.